For centuries, humans have gazed at the stars, yearning to explore the vastness of the cosmos. Long before spacecraft pierced the atmosphere or telescopes unveiled distant galaxies, artists wielded brushes, pencils, and imagination to carry us to other worlds. Space art—sometimes called astronomical art—has the extraordinary power to make us feel as though we’re standing on the rugged plains of Mars, drifting through Saturn’s rings, or orbiting an exoplanet light-years away. It’s more than mere illustration; it’s a portal to the unknown, a bridge between science and the human spirit.

Masters of the Cosmic Vision

Among the luminaries of space art, Chesley Bonestell stands as a titan, often dubbed the “father of space art.” Born in 1888, Bonestell’s meticulously detailed paintings—like Saturn as Seen from Titan—brought extraterrestrial landscapes to life with such realism that viewers could almost feel the icy chill of a distant moon or hear the silence of a Martian canyon. His work in the mid-20th century, blending scientific accuracy with artistic flair, inspired generations to dream of space travel. Other giants, like John Harris, with his sweeping depictions of futuristic spacecraft, and Chris Foss, whose bold, colorful starships defined science fiction aesthetics, have also left indelible marks on the genre. Ron Miller, a modern master, continues this legacy, chronicling space art’s evolution in works like The Art of Space. These artists didn’t just paint pictures—they opened windows to the solar system and beyond.

A Collective Dream: The International Association of Astronomical Artists

Space art isn’t a solitary pursuit; it thrives in community. The International Association of Astronomical Artists (IAAA), founded in 1982, stands as a testament to this. This organization unites creators worldwide who share a passion for visualizing the cosmos. Through workshops, exhibitions, and collaborations with scientists, the IAAA promotes space art as a tool for education and inspiration. Their mission echoes a profound truth: art can make the invisible tangible, turning abstract data from telescopes into vivid scenes that stir the soul. Whether it’s a painting of Jupiter’s swirling storms or a digital rendering of a hypothetical exoplanet, the IAAA ensures that space art remains a vibrant force in our collective imagination.

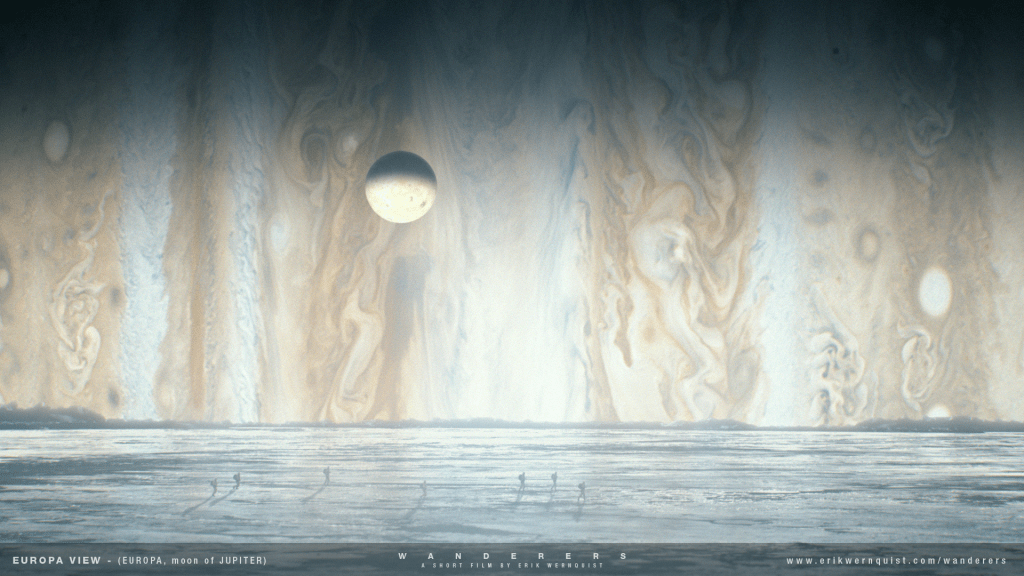

The Philosophical Thread: Wanderers and Wonder

At its core, space art carries a philosophical weight—a reflection of humanity’s innate drive to explore. Carl Sagan, the beloved astronomer and storyteller, captured this beautifully: “We are explorers… born to wander, to seek, to understand.” This sentiment finds a stunning embodiment in Erik Wernquist’s short film Wanderers (2014), a four-minute masterpiece that feels like a lifetime of cosmic travel. Narrated by Sagan’s voice, drawn from his book Pale Blue Dot, the film pairs breathtaking CGI with a haunting score by Christian Sandquist. It opens with a lone figure gazing at the stars from Earth, then catapults us across the solar system: humans drift in balloon-like habitats above Venus’s toxic clouds, skydivers plunge through Titan’s orange haze with Saturn looming overhead, and explorers leap across the jagged cliffs of Uranus’s moon Miranda. A standout sequence shows a massive rotating space station orbiting Earth, its artificial gravity a testament to human ingenuity. Each scene is grounded in real science—Wernquist consulted planetary data to ensure accuracy—yet feels otherworldly, almost spiritual. Watching Wanderers, you don’t just see these places; you feel the weightlessness, the thrill, the quiet majesty. It’s a call to action, a vision of humanity’s future that lingers long after the screen fades.

This philosophical connection deepens in NOORDUNG: A Voyage Through Our Solar System (4K), a cinematic journey produced by the European Space Agency. Named after Herman Potočnik Noordung, the Slovenian engineer who envisioned geostationary satellites and space stations in his 1929 book The Problem of Space Travel, this film is a visual love letter to our planetary neighborhood. Clocking in at over 20 minutes, it sweeps viewers from the Sun’s fiery corona to the Kuiper Belt’s icy fringes, all in crisp 4K resolution. Mercury’s cratered surface glows in harsh sunlight, Venus’s sulfuric clouds churn in eerie yellow, and Jupiter’s Great Red Spot swirls like a cosmic hurricane. A highlight is the descent into Saturn’s rings, where ice particles glisten against the planet’s pastel bands, accompanied by a minimalist soundtrack that amplifies the silence of space. The film’s pacing is deliberate, almost meditative, inviting contemplation of each world’s unique character. It’s not just a tour—it’s an experience, making you feel as though you’re aboard a silent probe, witnessing the solar system’s grandeur firsthand.

From Screen to Page: Scavengers Reign and 2001 Nights

Space art extends beyond the canvas into storytelling, where it continues to transport us. The TV series Scavengers Reign (2023), a 12-episode animated gem originally aired on Max, plunges viewers into the alien biosphere of Vesta, a planet as mesmerizing as it is deadly. The story follows the crew of the damaged freighter Demeter 227, stranded after a botched mission. What sets Scavengers Reign apart is its art direction, helmed by creators Joseph Bennett and Charles Huettner. Vesta’s ecosystem is a kaleidoscope of strangeness: towering fungal spires pulse with light, creatures with translucent bodies stalk through violet forests, and parasitic organisms twist into grotesque forms. In Episode 3, “The Wall,” a character navigates a canyon where carnivorous plants snap at glowing insects, their movements fluid yet alien. Another standout, Episode 7, “The Cure,” features a telepathic entity that merges with a survivor’s mind, visualized as a shimmering, amorphous mass. The show’s palette—rich purples, sickly greens, and stark whites—evokes a painterly quality, reminiscent of Bonestell’s moody landscapes. It’s unrelentingly immersive; you feel the humidity, the danger, the awe of a world that’s alive in ways Earth never could be. Scavengers Reign is space art as a living, breathing narrative, proving the medium’s power to haunt and inspire.

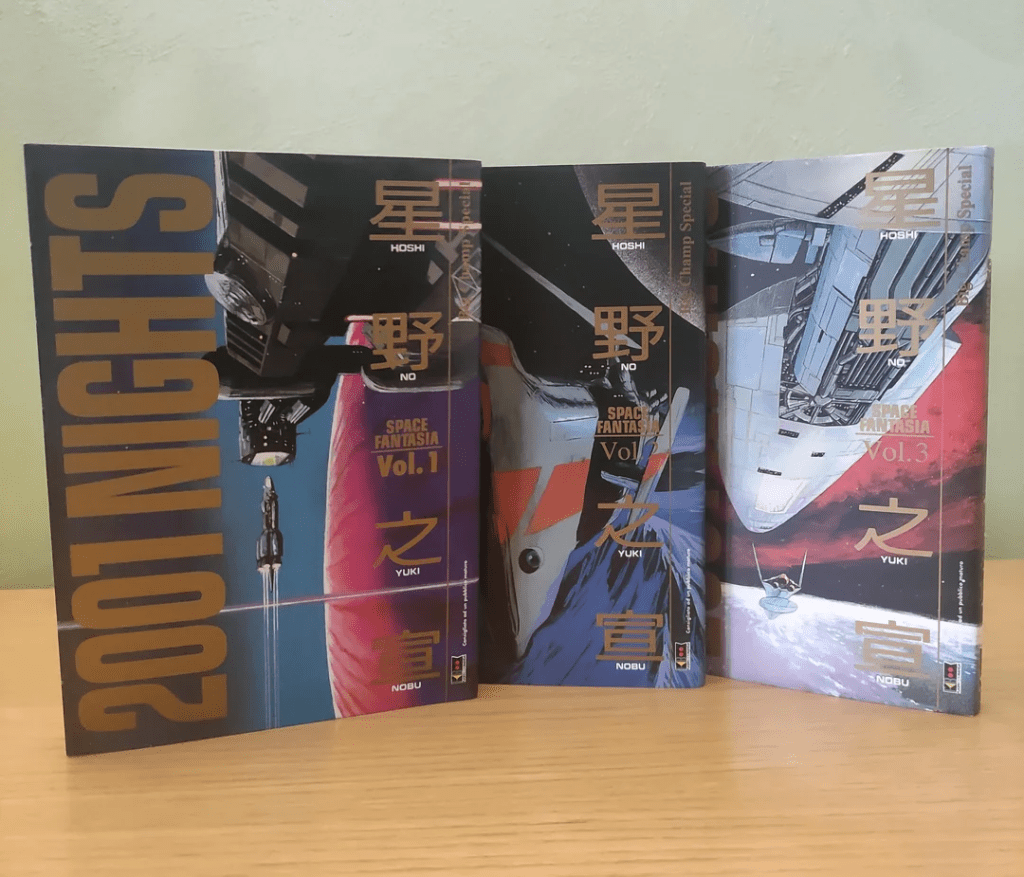

Similarly, Hoshino Yukinobu’s manga 2001 Nights (1984-1986) weaves space art into a tapestry of human ambition and cosmic mystery. Spanning 19 standalone yet interwoven stories across three volumes, it’s a sprawling epic of humanity’s stellar diaspora. Hoshino’s meticulous linework captures the sublime and the intimate: the curve of a spaceship’s hull, the glint of a distant star, the dust of an alien plain. In “Night 1: Earthglow,” a lunar base hums beneath Earth’s reflected light, its domes dwarfed by the void—an image so vivid you can almost hear the hum of machinery. “Night 11: Planetfall” depicts a descent onto a red-hued exoplanet, its jagged peaks and twin suns rendered with stark beauty; you feel the crunch of boots on foreign soil. “Night 16: The Sea of Silence” explores a derelict station orbiting a dead world, its corridors shadowed and desolate, evoking existential dread. Inspired by 2001: A Space Odyssey and classic sci-fi, Hoshino blends hard science—orbital mechanics, terraforming—with philosophical depth: What does it mean to leave Earth? To find life? To lose ourselves in the stars? Each panel is a work of art, transporting readers to places both wondrous and melancholic, a testament to manga’s ability to rival any canvas.

Why It Matters

Space art—whether painted, filmed, or drawn—does more than decorate; it inspires. It lets us walk on Pluto’s icy plains, sail through asteroid belts, or gaze at an exoplanet’s twin suns, all without leaving home. It connects us to the universe and to each other, reminding us that exploration isn’t just physical—it’s emotional, intellectual, spiritual. As Sagan said, we are wanderers, and through the works of Bonestell, the IAAA, Wernquist, and others, we wander still. So next time you watch Wanderers, lose yourself in Scavengers Reign, or flip through 2001 Nights, let yourself feel the journey. The cosmos is calling—and art is our ticket there.

Leave a comment